Thomas is an operational media specialist with the Bureau’s Operational Projects Unit (OPU), a small team within the FBI Laboratory that provides specialized visual and technical support to investigations. Among its duties—photography, 3D scanning, and courtroom exhibits—Thomas’ niche is unique: building forensic scale models of crime scenes. They are exacting in their accuracy, haunting in their detail, and designed for one purpose: to make the facts undeniable.

“Our basic tenet is to record data and document the crime scene so that we can tell the story later on as to what happened,” Thomas said.

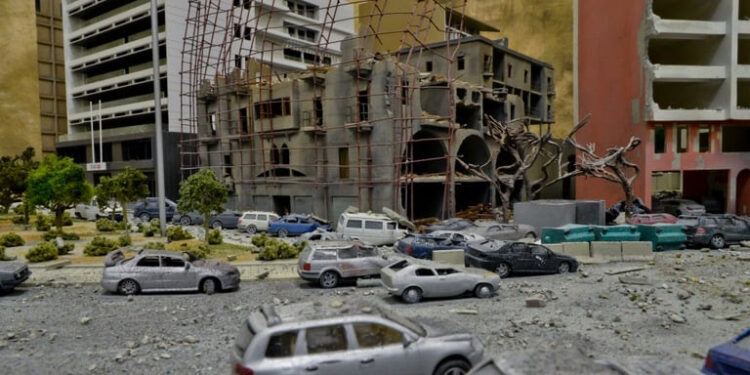

The models, typically no larger than a tabletop, have been used in cases involving bombings, homicides, and kidnappings—scenes too sprawling or chaotic to be conveyed by photographs or testimony alone. In the courtroom, they function as three-dimensional maps that turn crime scenes into something jurors can see and grasp.

But they’re not artistic renderings. They’re forensic reconstructions.

“It’s not my interpretation,” Thomas said. “It’s based on the data. If I can’t measure it, it doesn’t go in the model.”

OPU created models of buildings that were affected by the bombing assassination of former Lebanon Prime Minister Rafic Hariri in 2005. “We can’t take the jury or the people that are testifying to the crime scene,” says Bob Thomas, an operational media specialist in OPU. “So, it has to make the person feel that they are viewing the crime scene.”

Similarly, every component must be verifiable. “If I can’t document something in the room or in the scene, I won’t include it in the model because I can’t testify to it,” he said.

Thomas and his team begin by collecting exhaustive measurements from the field, often using laser scanners, drones, and survey equipment, along with traditional tools like tape measures and sketch pads. That information feeds into drafting software, which generates technical schematics. Only then does the physical build begin.

“I will build that model in my mind long before I cut any pieces,” he said. “I’m compiling all this information in my head and actually constructing it in my head before I can go to the computer and draw it up.”

A scale model of a Cleveland, Ohio, house in the case against Ariel Castro, who abducted young girls between 2002 and 2004, was built so that it could reveal details about the home’s interior rooms.

The objectivity is a non-negotiable part of the process and final product. Prosecutors may request the models, but the defense has equal access.

“It has to be fair and accurate,” Thomas said. “I can’t fudge it because I’m trying to influence the outcome one way or the other. I’m just showing you what’s there. You decide what you think.”

That rigor comes from an earlier career in engineering. Before joining the FBI, Thomas spent years reconstructing vehicle crashes for a major automaker, a role that demanded mathematical precision and an unflinching adherence to evidence. The transition from crash sites to crime scenes was natural: both require turning fragments of fact into something whole, something that can withstand scrutiny.

“There’s a craftsmanship involved in putting these things together,” Thomas says. “And it’s not just glueing pieces together; it’s figuring out how to build that model.”

OPU itself plays a similar role at the Bureau. Part investigative support, part visual documentation team, its specialists are often deployed to complex cases where accuracy and clarity matter most— major crimes that may end up before a jury.

Even as OPU, prosecutors, and courts experiment with digital animation and virtual reality to help juries understand crimes scenes, Thomas says some people respond better to physical models than flat-screen monitors.

“In essence, it’s still a two-dimensional image when you’re looking at it on a screen,” he said. “Whereas when you get something physical—well, it’s right there in front of you. You can relate to it.”

OPU unit chief Suzanne Brown agrees there’s always going to be a place for physical models. “When you can look at a model from above, you can see things differently,” she said. “You can see connections you didn’t see before. The model puts it all together.”

The Operational Projects Unit built a demonstrative model of a house for a state trial in the case against Bryan Kohberger, who was sentenced this year to multiple life terms for murders of four people in 2022 in Moscow, Idaho.

A model of the catamaran in the case of Lewis Bennett, 42, a dual citizen of Australia and the United Kingdom, who was sentenced in 2019 for killing his wife, Isabella Hellman, while on board a sailing vessel on the high seas.

A juror can walk around a model, trace sight lines, and realize that a witness positioned in one spot could not have seen what they claimed. Such moments are difficult to ignore—and even harder to challenge.

“That’s one of the biggest benefits of physical models is line of sight,” Thomas said. “That’s why we do this.”

For Thomas, who builds scale models of World War II ships in his spare time, the satisfaction is personal, too. “When I’m done with a project, I have something tangible that I can lay my hands on,” he said. Unlike the fleeting nature of digital renderings, his models endure—solid, measurable, and permanent.

Though the work brings him close to scenes of violence, he compartmentalizes, zeroing in on the technical puzzle. “I have to look beyond the body,” he said. “I’m interested in the couch.”

In a profession defined by impermanence—crime scenes cleared, memories contested—Thomas creates objects that last. In the end, he and his team give the FBI an extraordinary tool: a way to present the clearest, most truthful story possible.

“Just about everything that we do impacts somebody else,” Thomas said. “So, we strive to be as accurate, be as complete, to produce any kind of product that will be helpful in getting the point across.”